‘If I lost, I was determined to get them back and beat them. Losing made me more determined.’ Emile Griffith

Emile Alphonse Griffith was born on 3 February 1938 on the U.S. Virgin Island of Saint Thomas. Shortly after birth, his father took off and unfortunately, the most prominent male figure in his childhood memories was a man who molested young Emile, traumatising and emotionally scaring the youth for life.

Griffith’s legacy is remembered by many for a few reasons - namely, being involved in a fight which resulted in his opponent’s death, but also his sexual orientation. What many fail to initially mention is that he was a multi-weight world champion who was only stopped twice in 112 professional fights.

At the age of 19, Griffith moved to the bright lights of New York, working as a stock boy at a hat factory run by former amateur boxer, Howard Albert. Despite setting his heart on a future as a milliner, one day, Griffith was working shirtless, when Albert spotted his physique and encouraged him to try boxing at his friend’s gym, run by non-other than Gil Clancy. This was the start of an incredible friendship and partnership between the trio, which would see Griffith managed and trained by the pair. Young Emile went from dreams of making hats to making pugilistic history.

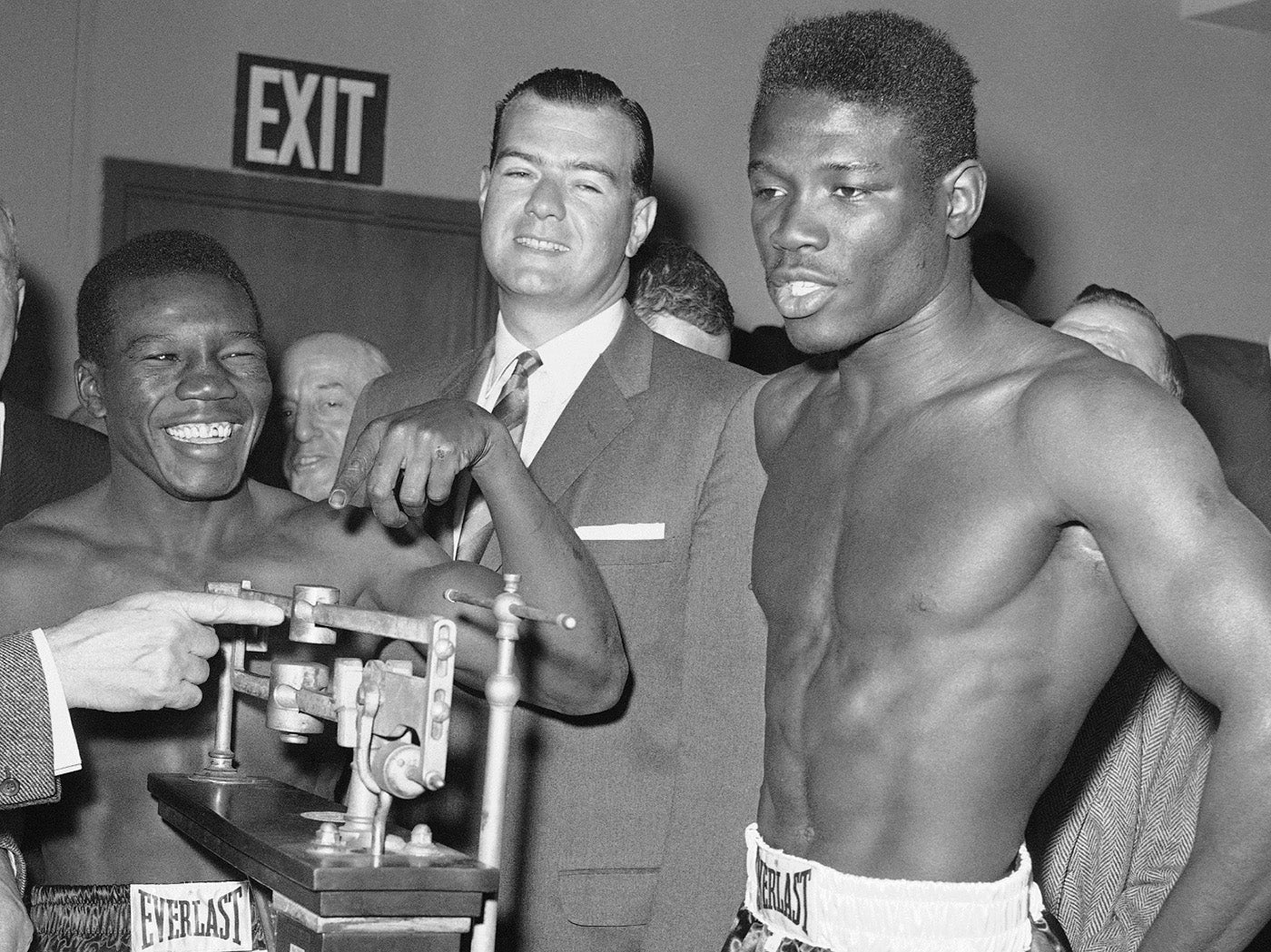

Within months of first donning the gloves in 1957, Griffith reached the finals of the welterweight division, but was defeated by Charles Wormley, who fought out of the Salem Crescent Athletic Club. However, in 1958 Emile’s fistic trajectory started to rise at a step gradient. Still competing in the 147lbs division, Griffith won three tournaments on the bounce, namely, the New York Daily News Golden Gloves Championship, where he defeated Osvaldo Marcano on 24 March 1958, the Intercity Golden Gloves Championship against Dave Holman and lastly, the New York Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions.

Guided by Clancy and Albert, the 20-year-old, standing a touch over 5ft 7 inches, made his professional debut on 2 June 1958, defeating Joe Parkham on points at St. Nicholas Arena, New York. Over the next 11 months, Griffith fought a further 11 times at the same venue, bringing his record to 12-0, with five stoppages.

On 7 August 1959, Griffith headlined at Madison Square Garden against the former Cuban welterweight champion, Kid Fichique, winning a comfortable points decision over 10 rounds. On the undercard was another Cuban by the name of Benny Kid Paret, who would play a big part in Griffith’s future.

Two months later, Griffith lost his first pro contest against Randy Sandy (great name) via split decision. Undeterred by the loss, the Virgin Islands native fought a further 10 times over the next 14 months against some study opposition, including world title challenger and Commonwealth champion, Willie Toweel, bringing his record to 22-2.

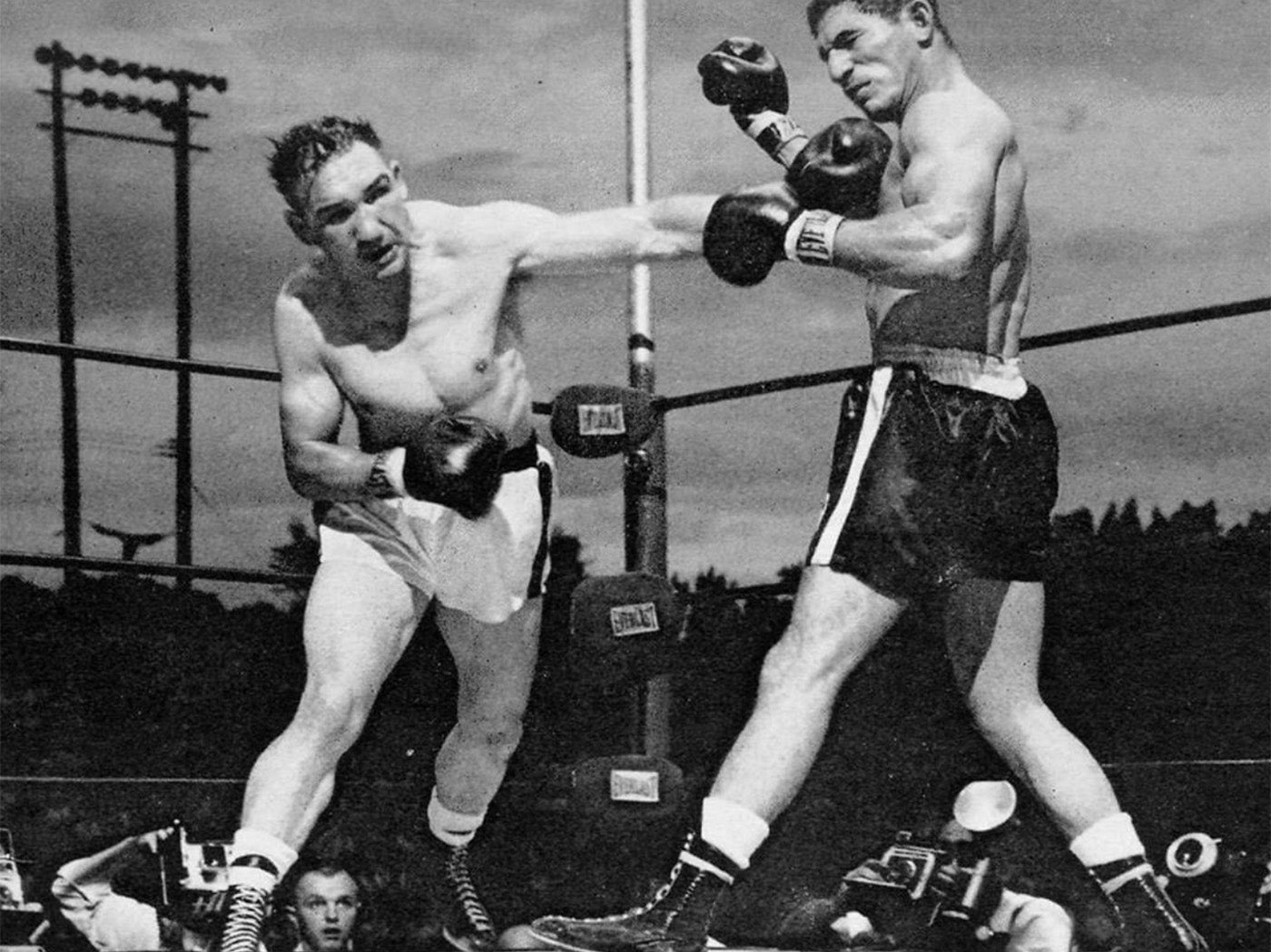

Less than three years after turning professional, on 1 April 1961, Griffith took on the world welterweight champion, Benny Kid Paret at the Convention Centre, Miami Beach. One minute and 11 seconds into the thirteenth stanza, Griffith stopped Paret, in a contest which was neck a neck up to that point, with one judge edging it to Griffith, one to Paret and the other who saw it a draw. The pair would inevitably meet again very soon.

Griffith v Paret 1961

Griffith v Paret 1961

Two months later, Griffith defended his title against Mexican, Gaspar Ortega, knocking him down twice in the seventh round, before stopping him in the twelfth. The first title defence tasted that much sweeter, because the pair had locked horns in February 1960, which saw Griffith taking a split decision victory, whilst the crowd booed, believing Ortega had dominated the contest. Griffith took the decision out of the judges hands this time round.

On 30 September 1961, Griffith attempted to defend his welterweight crown against Paret at Madison Square Garden, in another brutal contest, which saw the Cuban clinch a split decision victory over 15 rounds.

Not one to lick his wounds, Griffith fought three times in the next five months, clinching victories in Bermuda, America and his native Virgin Islands. Inevitably, the rubber match with Paret was set up and the pair met for the third time on 24 March 1962 at Madison Square Garden. However, this time the mood was different going into the fight. Paret had thrown homophobic slurs at Griffith, calling him a ‘maricón,’ which was the English slang equivalent of faggot. At a later date, Griffith said in an interview with Sports Illustrated, ‘I like men and women both. But I don't like the words, homosexual, gay or faggot. I don't know what I am. I love men and women the same, but if you ask me which is better, I like women.’ You have to remember that homosexual behaviour was illegal in some form, in most states in America, right up until the 1970’s and Griffith had no issue in expressing his sexual tendencies, which caused him to endure some disgusting treatment from society throughout his existence. His admission of being bisexual was believed to have been the transparent cover up for being gay in an alpha male existence.

To say Griffith went into the third Paret fight enraged was an understatement. The fight kicked off in its usual high octane manner, which saw Griffith take an eight count in round six and was close to being stopped if the bell hadn’t sounded for the end of the round. From the seventh onwards, Griffith came out like a man possessed, unleashing suffocating volumes of punches on Paret in what can only be described as a merciless beating. Going into the twelfth round, Griffith was well ahead on points and knocked Paret our cold. The ropes unfortunately held up the unconscious Cuban, whilst Griffith took no chances and continued to unload his arsenal until the referee finally stepped in. The fight was being transmitted live by ABC and was so shocking that they refused to run a live boxing show for a further 20 years.

Unfortunately, Paret never regained consciousness and passed away 10 days later on 3 April 1962 at the Roosevelt Hospital. Many believed Griffith wanted to intentionally kill Benny, but this was far from the truth. Yes, he was angry, but he was no murderer. In the minutes and hours that passed immediately after the fight was halted, Griffith realised Paret’s condition was very serious and immediately headed to the hospital, albeit, he was never allowed access to see his foe. The fight was investigated by the New York Governor, Nelson Rockefeller and despite both Griffith and the referee being cleared for any wrongdoing, the Paret death is an episode that would haunt Griffith until his dying days.

Griffith said at a later date, ‘I kill a man and most people understand and forgive me. However, I love a man, and to so many people this is an unforgivable sin; this makes me an evil person.’ Thankfully, over 40 years after the tragedy, Griffith was able to meet with Paret’s son, who told Emile, ‘I need you to know something. There’s no hard feelings.’

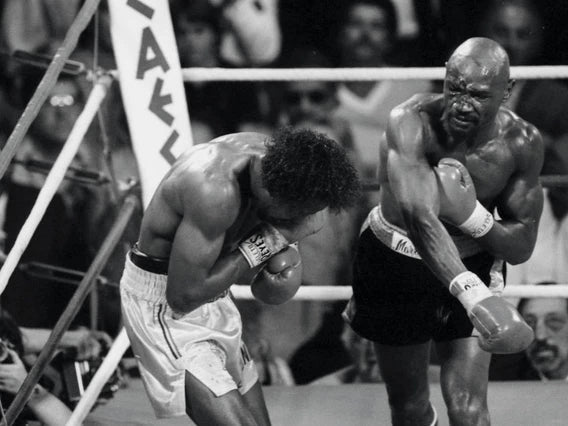

Four months after Paret’s passing, Griffith defended his welterweight strap against Ralph Dupas, defeating the New Orleans resident comfortably on points over the 15 rounds duration. In his next two fights, he fought north of 150lbs, defeating natural middleweights, Don Fullmer (Gene’s brother) and Denny Moyer, who he had previously lost to in 1960.

Griffith v Dupas 1962

Griffith v Dupas 1962

On 17 October 1962, Griffith beat Michigan boxer, Ted Wright in Vienna, Austria, to be crowned the world light middleweight champion, in a one-sided contest. However – the title was only recognised by the Austrian Boxing Board of Control, which meant in the public’s eyes, he was not a true champion. Ironically, as the alphabet soup of straps started to emerge, the first two officially recognised middleweight champions (WBA & WBC), from 20 October 1962 – 7 April – 1963, were……Denny Moyer and Ralph Dupas, both of whom Griffith had defeated back to back three months earlier.

After defending his Austrian recognised light middleweight world title against Dane, Chris ‘The Gentleman’ Christensen in Copenhagen, Griffith fought Cuban born Miami resident, Luis Rodriguez for the WBC world welterweight crown. The WBC title had already been awarded to Griffith in December 1962, as an inaugural title, but he never felt like the champion until he fought in the ring for it. Unfortunately, after 15 hard fought rounds, Griffith lost the fight on all three judges scorecards, however, not all was lost.

Just over two months later, on 8 June 1963, the pair locked horns again at Madison Square Garden. Once again, both fighters worked their trunks off in a close fight, but this time, Griffith did enough to grind out a split decision victory and in doing so became the new WBC world welterweight champion.

Griffith fought three more times in 1963, in non-sanctioned contests, one of which included a shock defeat against hard hitting Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter on 20 December, which saw Emile hit the canvas twice, before the contest was called to a halt in only two minutes and 13 seconds of the opening round.

1964 saw Griffith hit the road as he travelled to Australia, Italy, Hawaii, Las Vegas and even a couple of visits to the UK. Emile added five further victories to his CV, which included one no-contest, a title defence and rubber match victory over Luis Rodgriguez, plus a points defence over Brian Curvis at the Empire Pool, Wembley, which saw Curvis hist the canvas in rounds six, 10 and 13. Two months after beating Brian, Griffith beat fellow Brit, ‘The Dartford Destroyer,’ Dave Charnley via ninth-round stoppage.

The year after was a mixed bag. Griffith lost his opening contest of the year against on points in a non-sanctioned fight against Manuel Gonzalez, followed two months later in March 1965 by a successful WBC welterweight title defence against Jose Stable. Two fights later he lost a points decision against old foe, Don Fullmer for the WBA American middleweight title, followed by three victories, which included another successful title defence against Manuel Gonzalez, avenging his loss earlier in the year.

Griffith only fought three times in 1966, which in current day terms would be considered a full quota for a world champion. However, it was certainly the quality of the fights that counted, not the quantity.

After a warmup fight in February 1966, on 25 April, Griffith defeated teak tough Nigerian, Dick Tiger to retain his welterweight crown. Three months later, on 13 July 1966, Griffith beat Joey Archer on a majority decision for the WBC world middleweight title, cementing his place in history as a two-weight world champion. It’s worth noting that Dick Tiger was a natural 160lbs fighter and former world middleweight champion and only eight months after his defeat to Emile, beat Jose Torres to become world light heavyweight world champion. He was far from a washed-up fighter and a further clash with Griffith down the line was inevitable.

Griffith’s time at middleweight was far from a flash in the pan. It would in fact be a defining period in his fistic career, which unfortunately was littered with some of the best middleweights to walk this planet. In another era, Emile may have ruled the 160lbs roost for several years.

Six months after winning the title against Archer, he rematched the New York native and once again won by a slim margin on points. Three months later, on 17 April 1967 at Madison Square Garden, Griffith lost his middleweight crown against future Hall of Famer, Nino Benvenuti in a barnburner of a contest. After being floored in the second round, Griffith repaid the favour to the Italian in the fourth round and the pair battled it out for the full 15, with Benvenuti taking a convincing points decision in what was 1967 Fight of the Year for Ring Magazine.

Over the next 11 months, Griffith and Benvenuti fought a further two times. On 29 September 1967, Griffith knocked down Benvenuti in the fourteenth and despite one judge seeing the contest a draw, the other two had Emile winning by four rounds. He was now a two-time middleweight champion.

Six months later, on 4 March 1968, the pair met once again at Madison Square Garden, in a contest which was down to the wire going into the championship rounds. Unfortunately for Griffith he hit the canvas in the penultimate round, which marginally swayed the judges Benvenuti’s way. This would be Griffith’s last fight as world champion, albeit he was still in the mix at world level for several years to come.

Over the next three years, Griffith extended his record to 70 victories, 11 losses, which included an unsuccessful attempt at the WBC welterweight title against Jose Napoles and a non-sanctioned victory over Dick Tiger.

On 25 September 1971, Griffith made a gutsy attempt to dethrone the new WBC middleweight king, Carlos Monzon in his backyard of Estadio Lunar Park, Buenos Aires. Monzon, possibly one of the best ever middleweights, had ripped the title away from Benvenuti with a twelfth round stoppage in 1970. Four months prior to facing Griffith, he fought Benvenuti once again, but this time crushing the Italian in three rounds. Despite giving it his very best shot, Monzon was far too much for 33-year-old Emile, who was stopped by the Argentinian in the fourteenth round.

Over the next three years, Griffith clocked up a further six victories, one draw and one disqualification loss (due to a low blow) and attempted to beat the iron fisted Monzon once again, but this time at the Stade Louis II, Monaco. Despite many writing Griffith off as the heavy ageing underdog, he put up a solid performance, taking Monzon the distance in a fight which saw two judges giving the Argentine victory by three rounds and one by two rounds.

On 18 September 1976, Griffith took on German, Eckhard Dagge for the WBC world super welterweight title. Since the last Monzon loss, Emile’s resume now read, 82 victories, 20 losses and two draws, which included losses against the likes of Tony Mundine, Vito Antuofermo and victories over Bennie Briscoe. At 38 years of age, Griffith was given little chance of upsetting the odds, but once again, he pulled out a standup performance against Dagge, losing a debatable majority decision in the German’s backyard.

Griffith fought a further six times, with his swansong being against Alan Minter in Monaco on 30 July 1977. Having just turned 39 years old, Griffith thankfully hung up the gloves shortly after. His record, in a career which spanned almost 20 years, was 85 victories, 24 losses and two draws. Let’s also not forget he was a very respected two weight world champion who was always willing to share the ring with the best of the best.

Griffith went on to help train a number of fighters, including world champions, Juan Laporte, James Bonecrusher Smith and Wilfred Beneitez and even had a brief stint in the late 70’s as the Olympic Danish boxing coach.

1990 saw Griffith rightly inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Director, Ed Brophy said of Griffith, ‘Emile was a gifted athlete and truly a great boxer. Outside the ring he was as great a gentleman as he was a fighter.’

Sadly, in 1992, Griffith was the victim of a savage and sickening homophobic beating in New York, which left him hospital bound for a substantial amount of time, recovering from life threatening injuries to his head and kidneys.

Emile Griffith died on 23 July 2013 in a care home in New York, at the age of 75 from kidney failure, relating to dementia and was buried in St Michael’s Cemetery in Queens, NYC. He was a fast punching world champion with great footwork, a beautiful jab and defensive skills to match, who would have been world champion in any era. No doubt about it.

Paul Zanon, has had 11 books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.