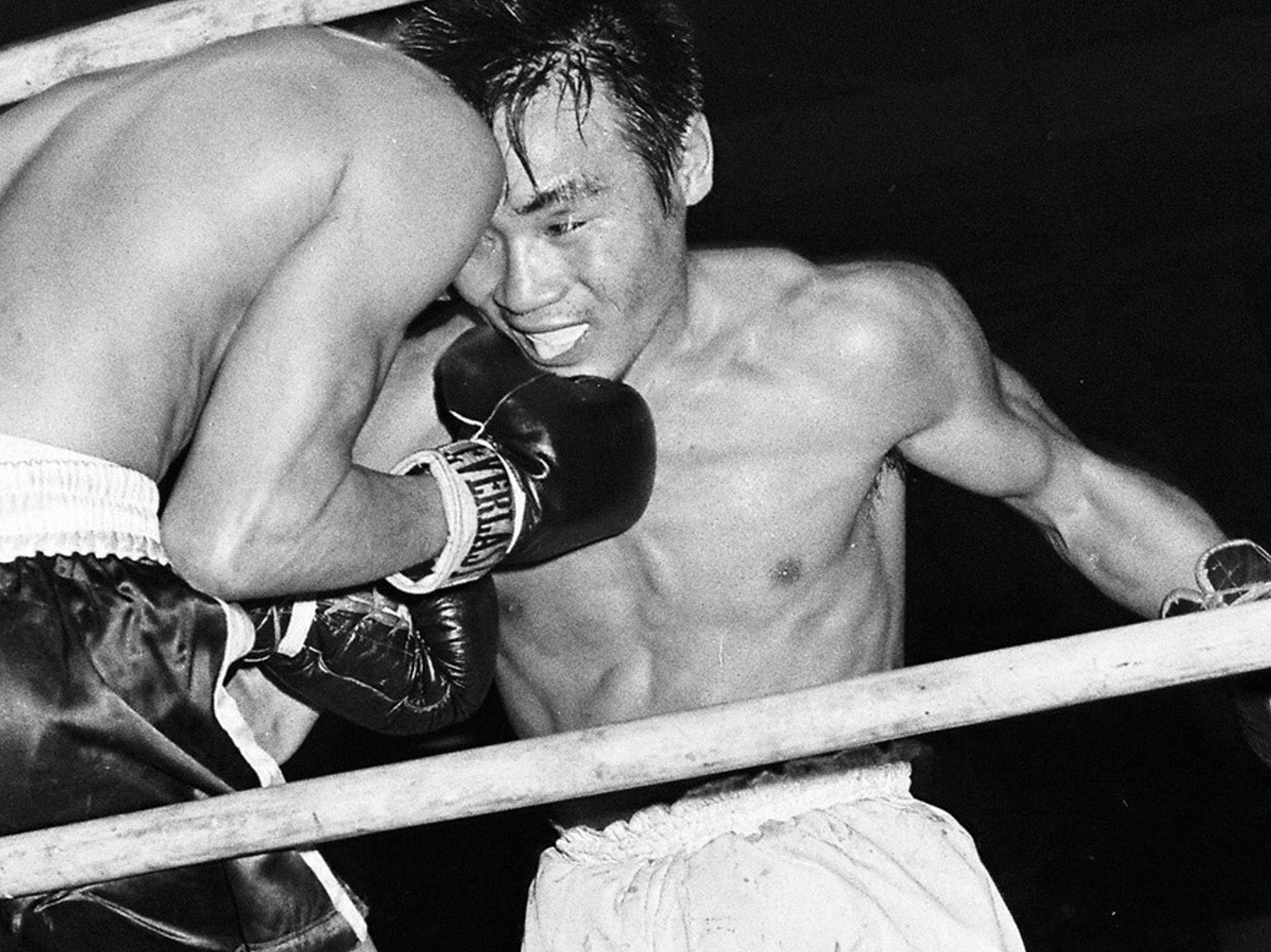

‘Harada had a lot of velocity in his arms, reaching to hit me recklessly several times. It was a style of his own that hindered the opponent when they tried to hit him.’

Eder Jofre, The Ring Magazine

Before Naoya Inoue, Masahiko Harada was considered the greatest Japanese boxer of all time by many.

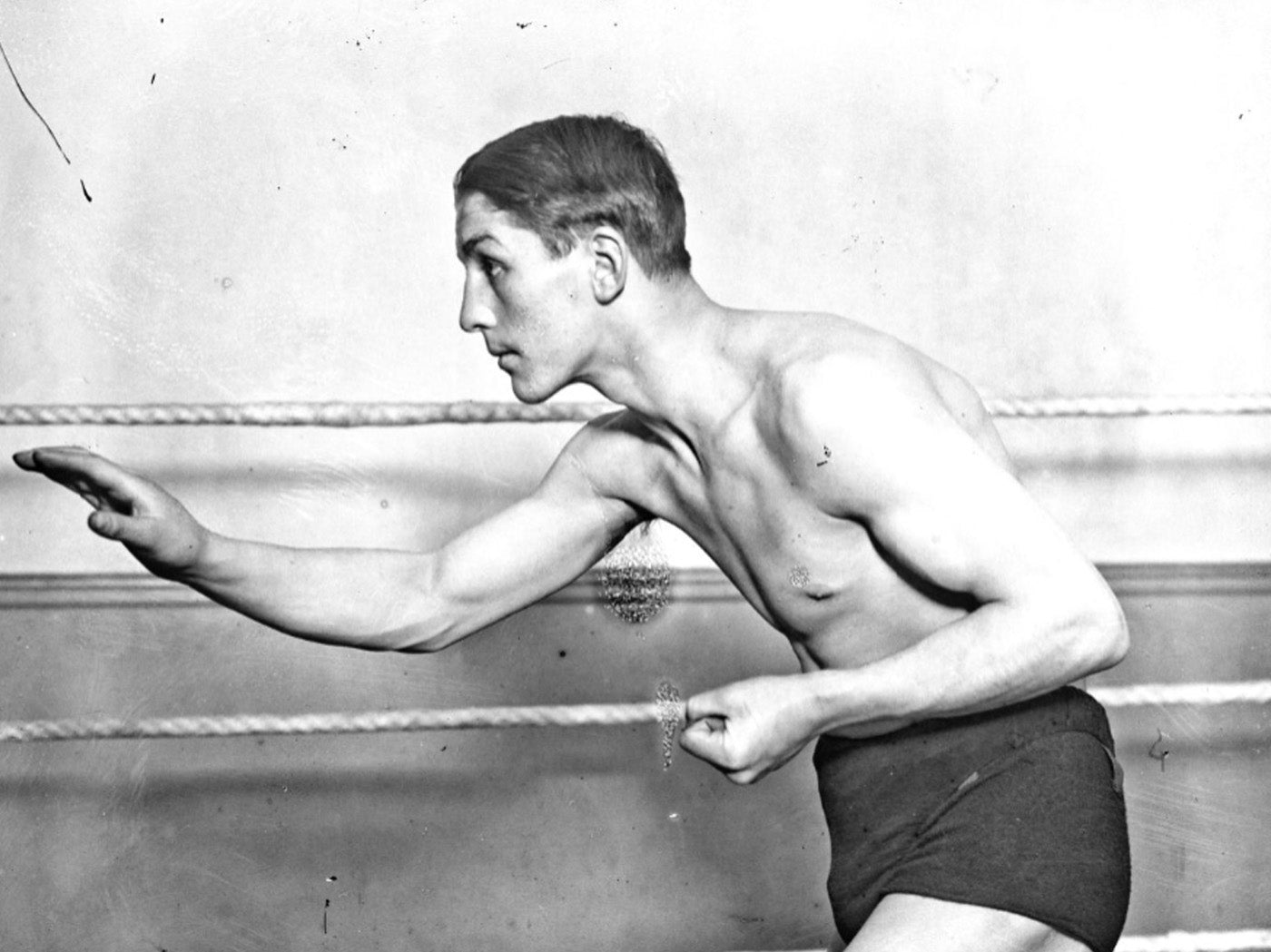

Born on 5 April 1943 in the Setagya Ward of Tokyo, Masahiko soon became earned himself the moniker of ‘Fighting’ Harada as he rapidly built of an impressive portfolio of fistic honours with his relentless attacking style. Sixteen-year-old Harada made his debut on 21 February 1960 against Isami Matsui, knocking out his fellow debutant in the fourth session and within eight weeks had already racked up five victories, including a very respected scalp in future referee, Ken Morita. By the end of the year he was 12-0, which included a notable win against future long reigning world flyweight champion, Hiroyuki Ebihara.

Harada’s first mark on his pro career came in his twenty sixth outing on 14 June 1962, against Mexican Edmundo Esparza, losing a tight split decision over the 10-round distance to the Chihuahuan. Undeterred by the loss, four months later on 10 October 1962, 5ft 3 inches Harada took on the reigning world flyweight champion, Pone Kingpetch at the Kokugikan arena in Tokyo. From the outset, Tokyo’s favourite fighting son controlled the Thai champion, leading the scorecards by a country mile. After tenderising Kingpetch for 10 rounds, 19-year-old Harada knocked out his foe in the eleventh and in doing so became the WBA world flyweight champion. Unfortunately, Kingpetch reclaimed his belt on 12 January 1963 after a dubious majority decision in his backyard of Bangkok.

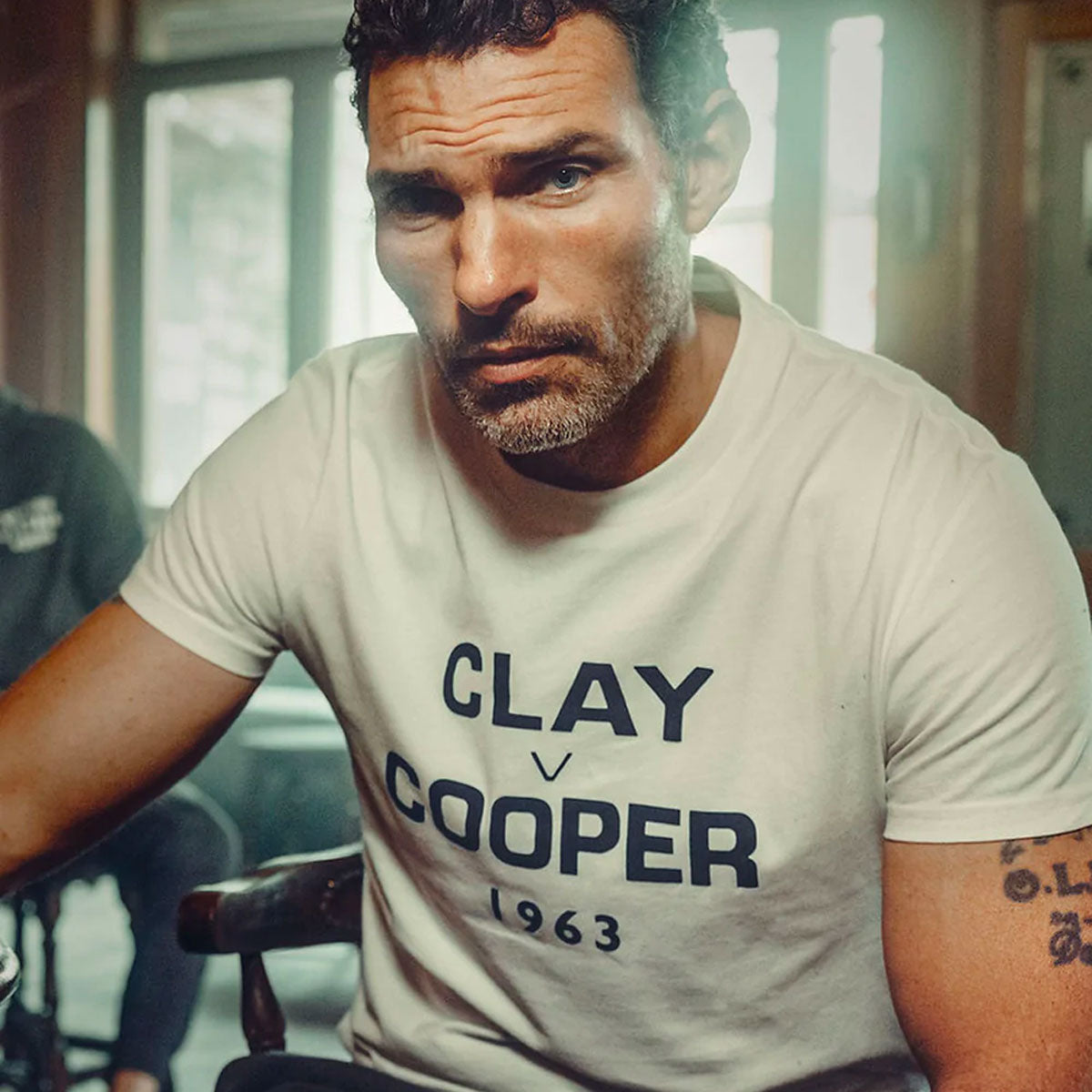

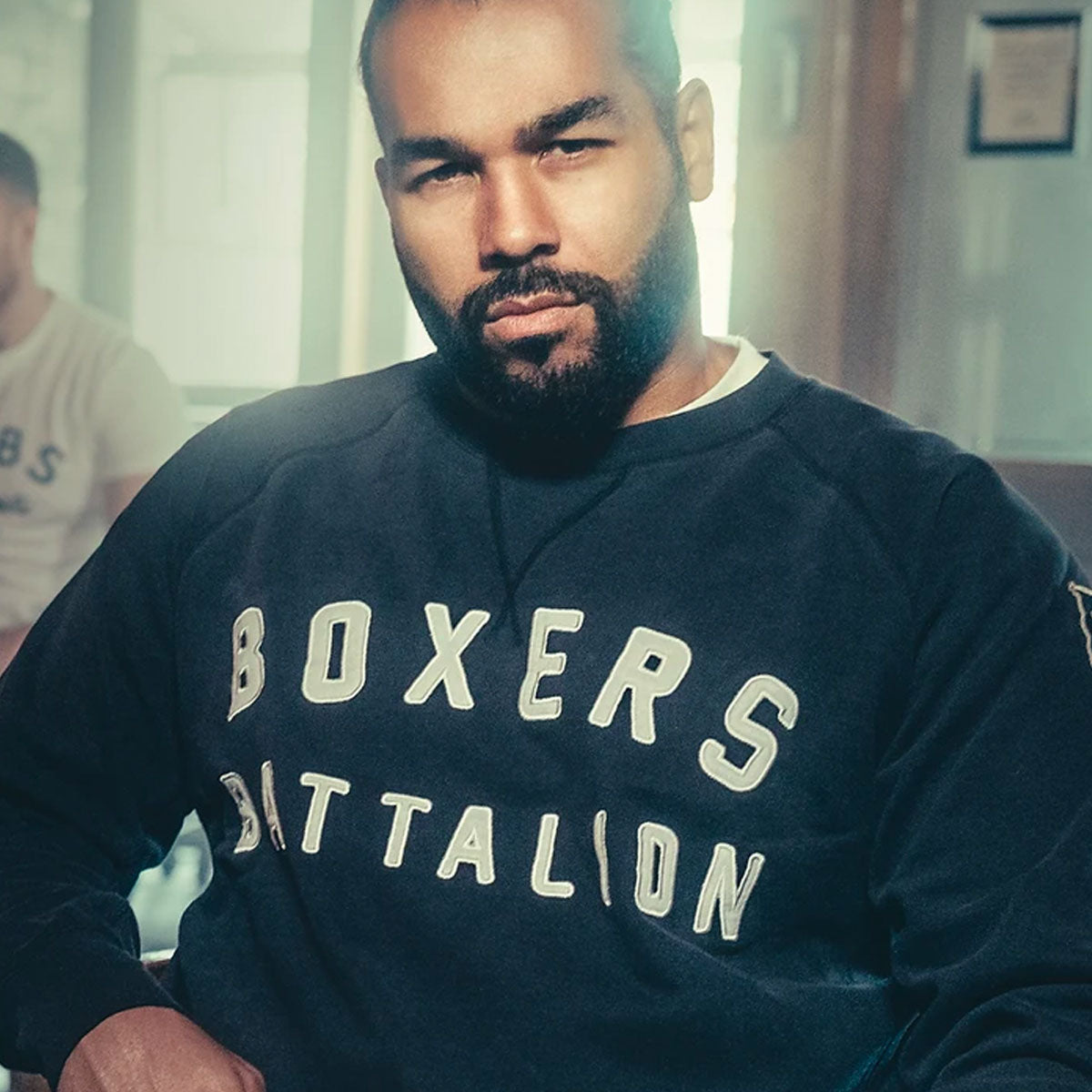

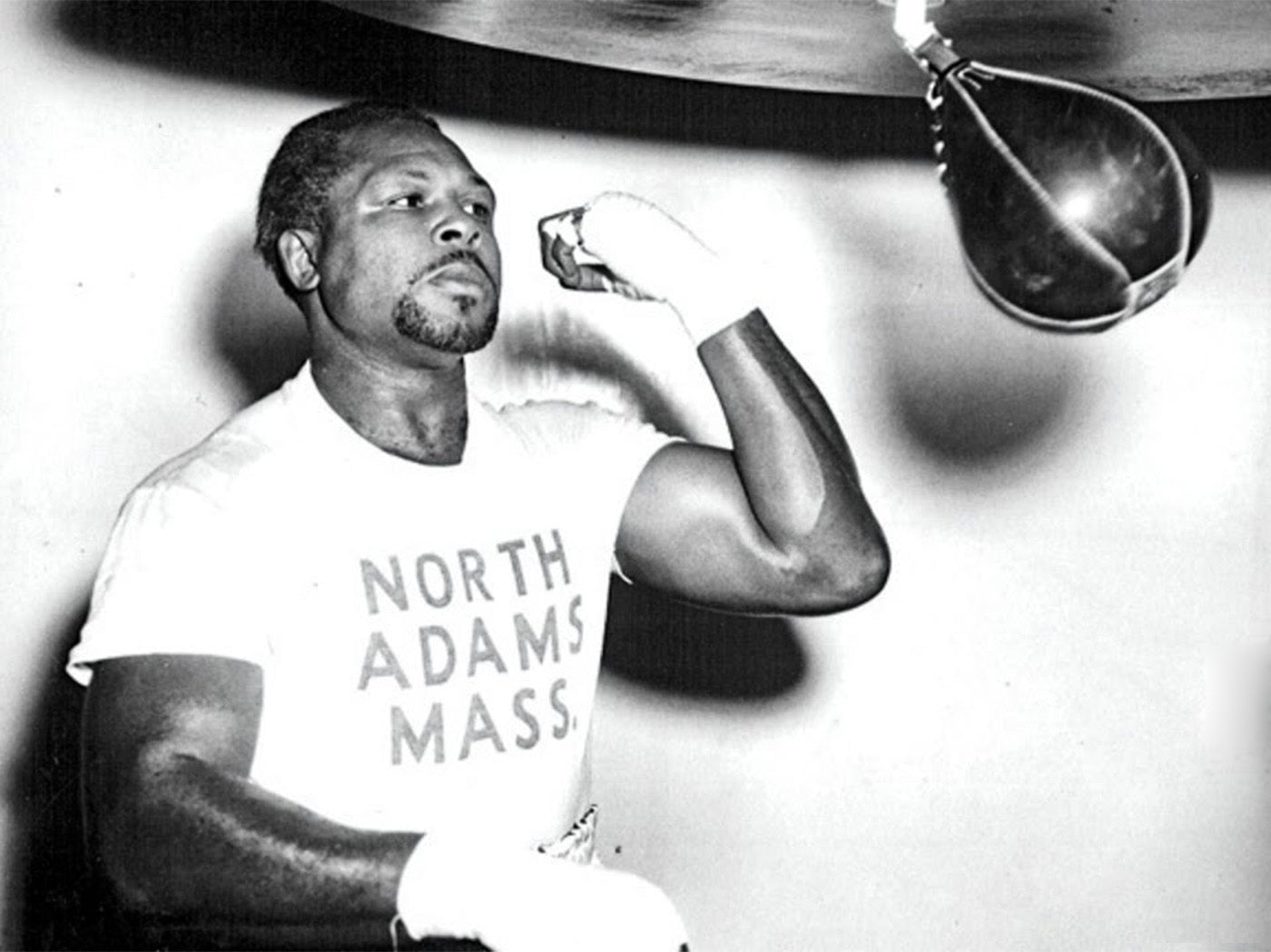

Following his defeat, a weight drained Harada bounced from super bantamweight to super featherweight in his next 12 outings, before taking a massive risk and challenging unbeaten, Eder Jofre on 18 May 1965. Harada now had 38 victories and three losses to his name, whereas the long reigning world bantamweight champion was bigger, heavier handed, had a string of KO’s on his resume and in his 50 fights he had never suffered defeat. None of this fazed Harada, who let’s not forget, was better known as ‘Fighting.’ After 15 hard earned rounds, Harada claimed a split decision victory at the Aichi Prefectural Gym in Nagoya, making him the WBA and WBC world bantamweight champion.

Fighting Harada vs Eder Jofre May 1965

Fighting Harada vs Eder Jofre May 1965

Basking in his unified glory, Harada clocked up three victories in the next nine months, including a world title defence against Merseyside’s Alan Rudkin on 30 November 1965, in front of 15,000 spectators at the Nippon Budokan, Tokyo. Despite going mano a mano against the Japanese champion for the full 15 rounds, Harada was simply to ring crafty and won by a wide points margin.

Fighting Harada vs Alan Rudkin November 1965

Intent on reclaiming his belts, Jofre stepped through the ropes of the Budokan on 31 May 1966. As opposed to previously when many though Harada had been fortunate to claim the nod from a hometown victory via a split decision, this time he beat the Brazilian on all three judges scorecards. In a career that extended to 78 fights, Jofre fought didn’t lose a single contest over the next 10 and a half years. In fact, seven years after his loss to Harada, the future hall of famer became WBC world featherweight champion. Without a doubt, those wins against the Sao Paolo resident were the most respectable of Harada’s career between two of the best bantamweights of all time. Harada said in an interview with Haris Mores at a later date, ‘When I found out that I was fighting him [Jofre], I was scared. He was a such a strong, hard puncher.’

Over the next 21 months, Harada won all seven of his contests, including two successful defences of his bantamweight straps against Mexican Jose Medel and Colombian Bernardo Carabello. Unfortunately, on 27 February 1968, Harada’s winning streak came to an end when he locked horns with Australia’s Lionel Rose, back at the Nippon Budokan. After 15 rounds, all three judges (which included old opponent Ken Morita), gave the decision to 19-year-old Rose, making him the first Australian fighter from an Indigenous background to be crowned world champion.

Fighting Harada vs Lionel Rose February 1968

Fighting Harada vs Lionel Rose February 1968

For the balance of Harada’s career, he struggled to make anything under 126lbs and campaigned at featherweight. Following the Rose loss, in the next 14 months Harada won four and lost one to nondescript opposition. Intent on regaining world champion status, on 28 July 1969, 12 days after the first man landed on the moon, Harada travelled to Sydney, Australia to take on reigning world featherweight champion, Johnny Famechon. Despite getting dropped in the fifth, Harada floored Famechon in the fourth, eleventh and fourteenth rounds. The legendary Willie Pep was guest referee and the sole judge that evening, initially scoring the outcome a draw. However, shortly after, an error in the scoring was discovered and Famechon was announced the victor with a tight 70-69 margin, to the crowd’s disgust. As opposed to those in attendance at the Sydney Stadium cheering in favour of the French born Australian, they booed the result and gave an almighty cheer for the Japanese challenger as he left the ring. The following day, the vast majority of the Australian press had the word ‘robbed,’ in the headline, referring to Harada’s injustice.

After demolishing Filipino, Pat Gonzales in eight rounds, on 6 January 1970, Harada rematched Famechon at the Metropolitan Gym, Tokyo. A combination of fighting in his own backyard and complacency from his previous fight instilled Harada with a false confidence sense of security that he would walk over the Australian in the rematch. Famechon on the other hand had never been so motivated to make a statement in a fight. Despite knocking Famechon down in the tenth round, Harada trailed on all three scorecards and was knocked out in the fourteenth round. This was Harada’s last professional boxing contest, retiring at a very modest 26 years of age.

Fighting Harada vs Johnny Famechon January 1970

Fighting Harada vs Johnny Famechon January 1970

In a professional boxing career that lasted little over 10 years, Harada became a two-weight world champion and knocked on the door of three divisions at a time when only 10 weight categories existed. He finished his career with 55 wins (22 KO’S) and two losses. Unsurprisingly, he was inducted into the international Boxing Hall of Fame in 1995 and in 2002, The Ring Magazine ranked him the 32nd greatest boxer of the previous 80 years.

Following retirement, Harada became the chairman of the Japan Boxing Association and also a hands-on Chairman of the Fighting Harada Boxing Gym, training fighters to become future champions. He grew extremely fond of his Australian fan base, but better still his two Aussie foes, Lionel Rose and Johnny Famechon. The trio would often be seen on the golf course together, which one would assume would always be a fun, yet competitive affair.

Harada, Famechon and Rose

Harada, Famechon and Rose

Harada went on to inspire a host of fighters, including Wilfredo ‘Bazooka’ Gomez, who openly admitted the Masahiko was an idol of his growing up and was over the moon when he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame alongside Harada in 1995.

Despite suffering a brain haemorrhage in 2004 whilst at the wheel of his car, Harada recovered and at the time of writing is still alive. In fact, in November 2019 he presented Naoya Inoue the Muhammad Ali trophy at the Super Arena, Saitama, Japan, after beating Nonito Donaire in the World Boxing Super Series. Some say it was like an informal passing of the torch from the former fighting legend many called the greatest of all time on Japanese shores. Imagine if the pair locked horns at bantamweight? We can only imagine.

Paul Zanon, has had 11 books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.