‘I would not like to be remembered as someone who amounted to do so much as an athlete, but who was good for nothing as a person. I couldn't stand that.’

Max Schmeling

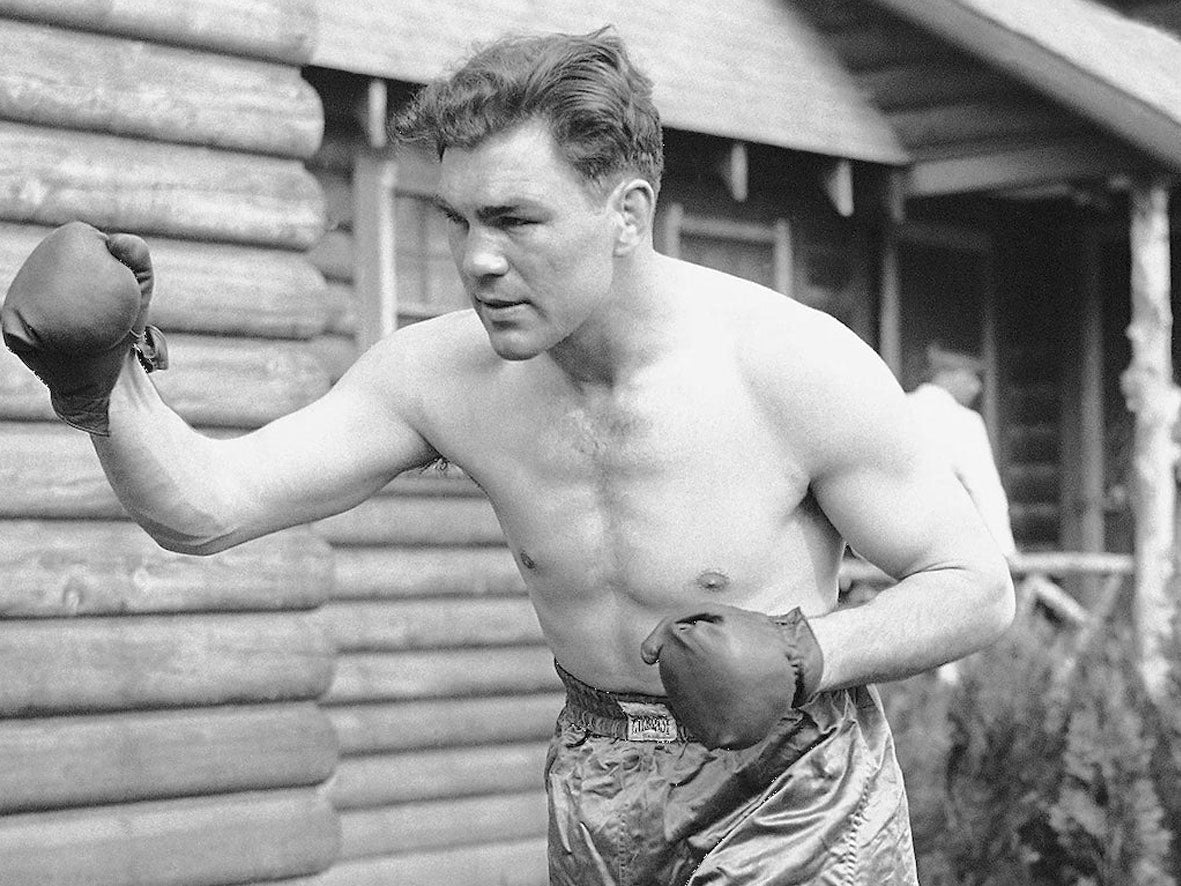

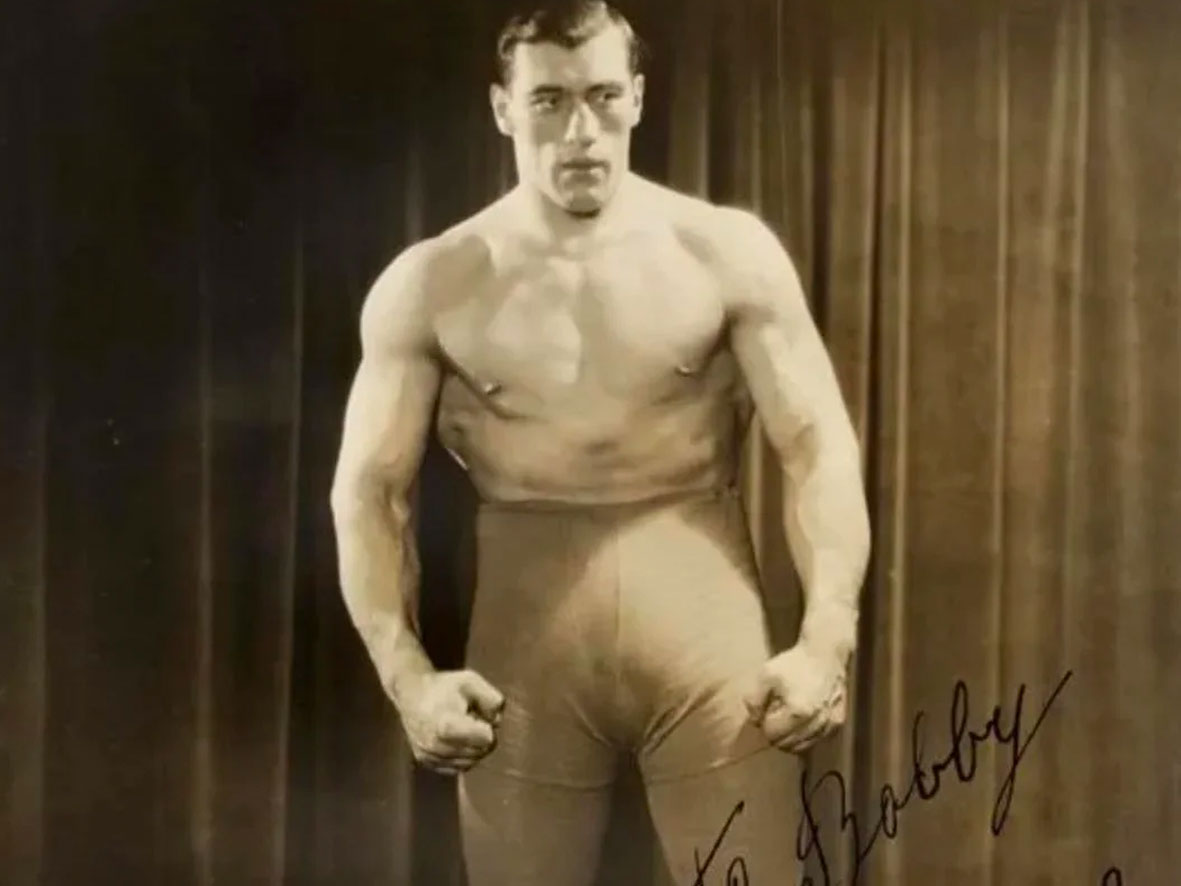

Maximilian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling, better known as Max or Maxey, was Germany’s first ever European and world heavyweight champion.

Born on 28 September 1905 in the Prussian province of Brandenburg to parents Max Sr and mother Amanda, 16-year-old Max grew a strong interest in boxing after watching a film of Jack Dempsey against Georges Carpentier with his father. Taken in by Dempsey’s style Schmeling modelled himself on The Manassa Mauler and soon started to compete as an amateur. Shortly after winning the light heavyweight division in the German National Championships, Maxey turned pro.

Eighteen-year-old Schmeling made his professional debut on 2 August 1924, in Tonhalle, Duesseldorf, knocking out Hans Czapp early doors and weighed a little under 170lbs (a touch over modern day super middleweight). By the end of the year he had notched up nine wins, eight by knockout, one points decision and one retirement loss against debutant Max Diekmann due an ear injury.

1925 hardly showed the form of a future world champion as Schmeling won six, drew two and lost two, which included a knockout stoppage from The Toronto Terror, Larry Gains. None of this mattered though because Germany’s favourite fighting son embarked on a 21-fight streak (20 wins, one draw), picking up those all important stepping stone straps along the way to world title contention. Perhaps one memorable milestone for Maxey in 1925 was sparring his idol Jack Dempsey, who was in preparations for defending his world title and was by all accounts impressed with the 19-year-old.

Schemeling’s first fight of 1926 was at the Kaiserdamm Arena on 12 February against old foe Max Diekmann. Eager to avenge his loss, Schmeling was only able to produce a lacklustre draw. However, as the stakes rose, the crowds started to see the best of Schmeling. After two first round knockout victories, they met for the third and final instalment of their trilogy at Luna Park, Halensee, but this time the German light heavyweight title was on the line. On 24 August, weighing in a touch over 173lbs, Schmeling disposed of Diekmann in 30 seconds, which not only stated his claim as the best 175lbs fighter in his homeland, but also announced him on the European stage.

Over the next nine months, Schmeling won nine fights on the bounce, with only one going the distance, but it was his next fight which elevated the 21-year-old into the limelight. On 19 June 1927, Max took on Belgian Fernand Delarge for his European light heavyweight strap. Despite weighing only a touch over 171lbs, Schmeling disposed of Delarge in the 14th of 15 scheduled rounds at the Westfalenhalle in Dortmund.

Schmeling finished the year with six further victories, including a title defence of his European and German light heavyweight straps against Hein Domgoergen, who was 79-3-6 at the time, and a well respected points victory over British and Commonwealth light heavyweight Gipsy Daniels. Unfortunately for Schmeling, after a very impressive first round knockout victory, retaining his European title against Michele Bonaglia (21-1-1 at the time), he was knocked out in the first round by Welshman Gipsy Daniels in the first round of a non-sanctioned contest.

By now, Schmeling was struggling to get below 180lbs and started to progress in the heavyweight ranks – albeit, as a small heavyweight. Six weeks after the Daniels loss, he took on the reigning German heavyweight champion, Franz Diener. The Berlin resident had been in with good company, including a loss to Larry Gains and a draw with Paulino Uzcudun. Later on he would also fight Primo Carnera twice, gaining victory on one occasion. However, on 4 April 1928, despite outweighing Schmeling by 12lbs, Diener lost his title on points over 15 rounds. The newly crowned champion now decided to head Stateside for those career defining fights which would ultimately give him that all essential traction towards a world title shot.

Schmeling made his debut at Madison Square Garden on 23 November 1928 against Joe Monte, stopping the Brockton resident in eight rounds. His arrival in America was polar opposite to his exit a decade later. He was an up and coming European fighter with no connections in the fight trade, but that all changed when he met esteemed boxing manager Joe Jacobs, who would become a close friend and confidant through a colourful decade.

After a points victory over durable Pennsylvanian Joe Sekrya on 4 January 1929 and a one round demolition against Pietro Corri, Schmeling locked horns with Slovakian born Johnny Risko, AKA ‘Cleveland Rubber Man,’ on account of his ability to absorb blows.

On 1 February 1929, Risko and Schmeling fought at Madison Square Garden in a barnburner of a contest. In the ninth round the referee stopped Risko from further punishment after a gruelling encounter for both fighters. It was the first time Risko had ever been stopped and the contest unsurprisingly won 1929 Fight of The Year for Ring Magazine.

Four months later Schmeling took on former European heavyweight champion, teak tough Spaniard Paulino Uzcudun, outpointing him over 15 rounds at Yankee Stadium. The German was now considered to be the No.1 contender for the world heavyweight title, but with Gene Tunney having recently retired, the title was now up for grabs.

On 12 June 1930, Schmeling took on Jack Sharkey for the vacant title at Yankee Stadium, however, the fight finished in a manner which neither fighter was happy with. In the fourth round, Sharkey let loose with a low blow to Schmeling’s groin, which rendered him incapable of continuing. Angered by the manner in which he acquired the world heavyweight strap and the negative media which followed him in the days and weeks after, Schmeling, now given the moniker of ‘Low blow champion,’ set about proving his worth.

Three weeks later he stopped Young Stribling in the 15th round at Municipal Stadium, Cleveland, before allowing ‘The Boston Gob’ a second chance on 21 June 1932 at Madison Square Garden Bowl, Long Island City, Queens. Unfortunately for Schmeling, he was on the bad end of a hometown split decision. One judge had it 10-5 for the German, with the other two giving Sharkey a marginal advantage on the scorecards. Straight after the fight the New York State Athletic Commission barred most of the individuals involved with the scoring skulduggery from ever being involved in a boxing contest again. On a positive note, Schmeling married movie star Anny Ondra and they remained wed until Ondra passed away in 1989.

In the meantime, Hitler’s ideology and anti-Semitic mindset was festering at rapid speed. As Max became a recognised name in the U.S., the world’s most repugnant dictator started to design moves for his unknowing political pawn

Three months after the Sharkey loss, Schmeling stopped the ‘Toy Bulldog,’ Mickey Walker in eight rounds, however, the next three fights proved to be hard work. On 8 June 1933 Schmeling lost to Max Baer on Jack Dempsey’s first promotional card, in front of over 53,000 people at Yankee Stadium. Unfortunately, the fight had already started to get overshadowed by political bias. Baer, a non-practising Jew, wore the star of David on his shorts as he went toe to with the German, who was already in Hitler’s vile slipstream as a reluctant Nazi mouthpiece. Despite the tenth-round stoppage, Schmeling gave a great account of himself and in what was a very competitive fight. The contest was Ring Magazine’s 1933 Fight of The Year and in his next fight, Baer stopped Primo Carnera to become world champion.

Eight months later Schemling lost a points decision to New Jersey tough man, Steve Hamas, then drew against old foe Paulino Uzcudun. Despite only fighting twice in 1935, Schmeling reappeared with a new found gusto, avenging his loss to Hamas with a ninth round stoppage and beating Uzcudun convincingly on points four months later. The German only fought once in 1936, but it was said fight which engrained him in boxing folklore for eternity.

On 19 June 1936, Schmeling took a huge risk taking on unbeaten Joe Louis who was taller, heavier, younger and had stopped 20 of his 24 opponents by this stage. In essence, Schmeling, a 10-1 underdog was out-of-date cannon fodder for the young gun, however, contrary to the majority, he had other plans.

At the weigh-in, Schmeling was very relaxed and wished Louis good luck. When asked by the media why he was so confident, Schmeling replied, ‘I see something,’ without divulging any information. The German had noticed that every time Louis threw a jab, his hand would drop and leave him open to an overhand right.

From the opening bell at Yankee Stadium, Schmeling worked out of a crouch with his chin tucked tightly into his left shoulder, thus making it difficult for Louis to land. However, the younger fighter’s jab did connect and caused a decent swelling of the German’s left eye in the opening stanza. Second round saw Louis unload his destructive left hook, however, Schmeling was comfortably moving with the motion, then countering with his right hand. Louis recalled the blow at a later date and said, ‘I thought I’d swallowed my mouthpiece.’

Entering the fourth round, Schmeling was down 3-0 on all of the scorecards, was cut under his right eye and was working with a partially closed left eye. Then came ‘that’ moment. As Louis flicked out a jab, Schmeling, who had patiently waited for his moment, saw the left hand drop and threw his trademark overhand right. The moment it connected, Louis hit the canvas for the first time in his career. Despite making a powerful onslaught in the tenth round, Louis was knocked out in the twelfth in front of 40,000 roaring fans. They had just been treated to Ring Magazine’s 1936 Fight of The Year. The winner of the fight had already been pencilled in to fight the reigning champion, James Braddock, but it never materialised, which forced Max back home.

Following the victory over Louis, Schmeling returned to Germany on board the famous Hindenburg Zeppelin. The vessel would perish in one of aviation’s most famous blazing disasters in 1937, which was perhaps a sign of things to come for the victorious German. On returning to his homeland, the fight was shown throughout the country and Schmeling was honoured with a number of parades organised by Adolf Hitler, who maximised the value of the boxer in his propaganda campaigns. Americans branded Max a Nazi, which saddened him deeply, even though he refused Hitler’s countless invites to be part of the Nazi party. In addition, against the instructions of Hitler who was making him out to be a Nazi hero with the Louis victory, Max publicly associated with German Jews and refused to sack his manager, Joe Jacobs who was an American Jew.

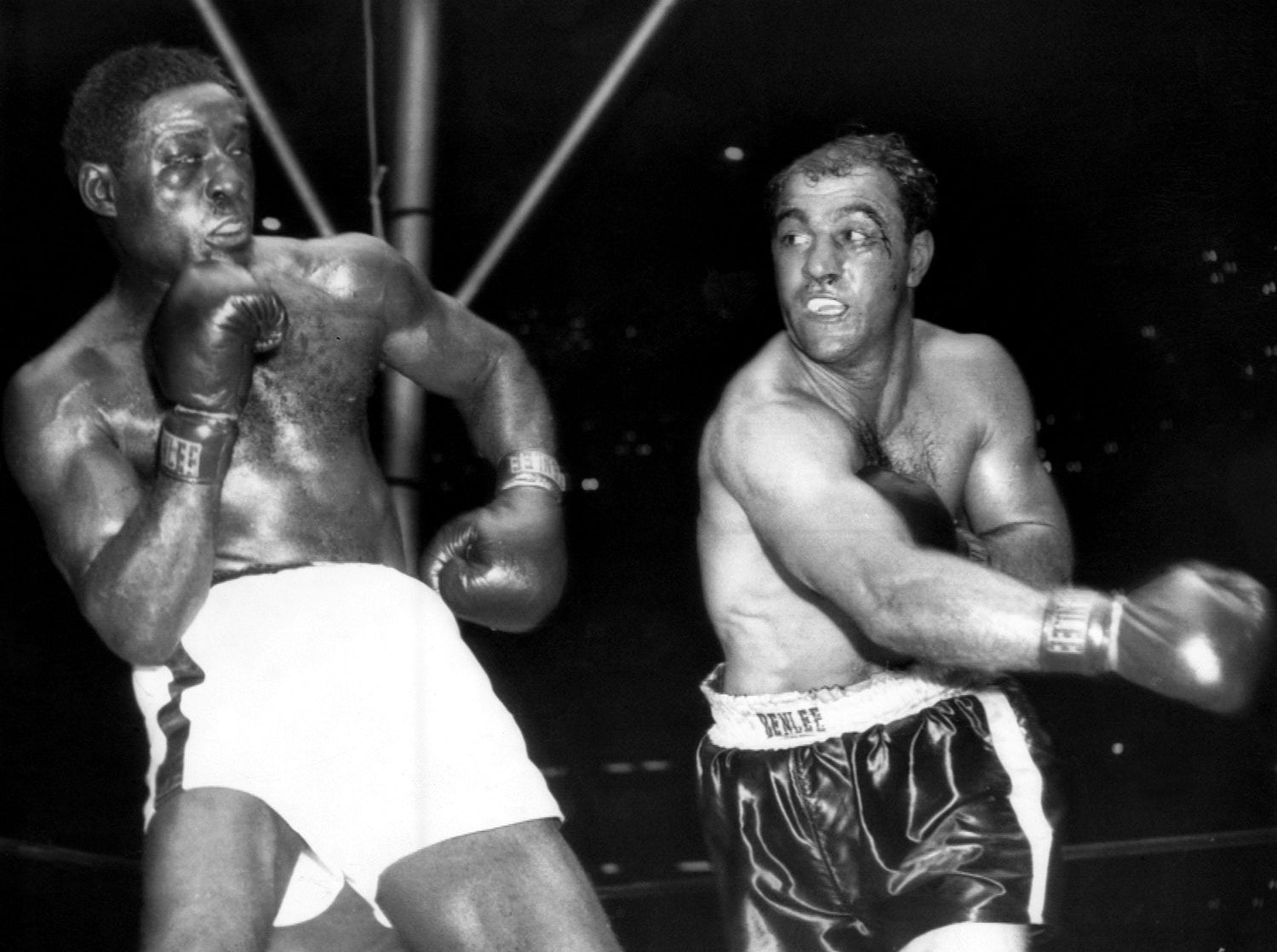

After three victories against nondescript opponents, Schmeling was set for the rematch against Louis on 22 June 1938 at Yankee Stadium. The American on the other hand had beaten 11 opponents, knocked out nine, become world heavyweight champion by knocking out James Braddock exactly one year to the day prior on 22 June 1937, not to mention defending the title three times.

With 70,000 fans in attendance this time, the fight had almost been marketed as good versus evil, with Louis being the golden boy. As Schmeling walked to the ring he was subject to a tirade of verbal abuse, Nazi salutes and a number of objects, including lit cigarettes, bottles and banana skins.

From the opening bell, Louis unloaded on Schmeling, hurting him with the first two punches. It was a one sided beating with no return from Schmeling which saw the contest halted after two minutes and four seconds. The German suffered a multitude of injuries including fractured vertebrae in his back and was put in an ambulance shortly after the final bell. In Hitler’s eyes, losing against Louis was tantamount to losing for The Third Reich. Schmeling had gone from being in every newspaper and publication in Germany to disappearing from the public eye, which suited him down to the ground.

Louis said after the fight, ‘I had nothing personally against Max, but in my mind, I wasn't champion until I beat him. The rest of it, black against white, was somebody's talk. I had nothing against the man, except I had to beat him for myself.’ Schmeling was also purely about the boxing and expressed that in an interview in 1975. ‘Looking back, I’m almost happy I lost the fight. Just imagine if I would have come back to Germany with a victory. I had nothing to do with the Nazis, but they would have given me a medal. After the war I might have been considered a war criminal.’

Later that year, as Hitler’s war on the Jews reached new spiteful heights, Schmeling hid two teenage sons of a friend of his, David Lewin at his apartment in the Excelsior Hotel in Berlin, telling reception that he was very ill and for nobody to come up and see him. Brothers Henry and Werner Lewin survived, with Henry moving to the US and becoming a big success in the hotel industry.

Two months before the start of World War II, on 2 July 1939 at the Adolf-Hitler-Kampfbahn in Stuttgart, Schmeling stopped Adolf Heuser in the first round to win the German and European heavyweight titles again. Unfortunately, as opposed to Louis who fought 15 times during the war, Schmeling didn’t fight again until 1947. Hitler in the meantime held a bitter grudge over Max and decided to have him drafted in the paratroopers and swiftly sent him on numerous suicide missions. Despite being wounded with shrapnel on the first day of the 1941 invasion of Crete, he received an Iron Cross for bravery and saw out his duty of service until 1943, where he was deemed unfit for service.

Appalled by Hitler’s dictatorship, Max visited a number of prisoner of war camps in Germany and did his utmost to help ease the conditions for American and Jewish captives. Once the war came to an end, British authorities cleared him of any Nazi war crimes which had been falsely connected to his name.

When Schmeling did return to the square ring after the war, it was purely for financial reasons. The 42-year-old was a mere shadow of his former self and despite winning three fights and losing two, Max hung up the gloves after a points loss to Richard Vogt on 31 October 1948. He retired with a very respectable 56 victories, which included 39 KO’s, 10 losses and four draws, not to mention being a two-weight German and European champion and also reaching the heights of world heavyweight king.

Post war and retirement, Schmeling and his wife Anny did everything they could to scrape by. Tobacco, mink and chicken farming provided a modest income, however, it was an approach from the soft drink giant Coca Cola in the 1950’s which proved to be pivotal in Schmeling’s fortunes.

By now, a former New York boxing commissioner had become a big wig in Coca Cola and was looking for a fresh face to re-introduce the brand back into Germany, post Nazi rule. Schmeling fitted the bill perfectly and after many meetings and he not only jumped on board as brand ambassador, but by 1957 Coca Cola had granted him control of operations in Hamburg. He went on to become president of Coca Cola in Germany and became possibly the most influential character of the company, right up to he stepped away, shortly before his passing.

Years after their epic fights, Schmeling tracked Louis in Chicago and visited him at his home. In an interview with the LA Times in 1988, Max recalled saying to his old foe, ‘‘Joe, you didn’t believe all those bad things they wrote about me, did you?’ He said he knew that it was all bull, and so we struck up a warm friendship.’ They remained close friends until Louis death in 1981. It was no secret that Louis retired broke and stayed penniless until he perished, and it was his old friend Max who paid for the majority of the funeral, in addition to being a pallbearer for his friend and foe.

Schmeling was Inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992 and died on 2 February 2005, six months shy of his 100th birthday. He remains the oldest lived heavyweight boxing champion in history.

In an interview with The LA times in the 1980’s, rising tennis star Steffi Graf asked how he maintained his popularity. Schmeling replied, ‘I told her that a smile doesn’t cost anything and your fans won’t forget it. And, most important, to keep both feet on the ground.’ That sums up the legend, Max Schmeling.

Paul Zanon, has had 11 books published, with almost all of them reaching the No1 Bestselling spot in their respective categories on Amazon. He has co-hosted boxing shows on Talk Sport, been a pundit on London Live, Boxnation and has contributed to a number of boxing publications, including, Boxing Monthly, The Ring, Daily Sport, Boxing News, Boxing Social, amongst other publications.